How to determine appropriate patient status and navigate observation-level care

How to determine appropriate patient status and navigate observation-level care

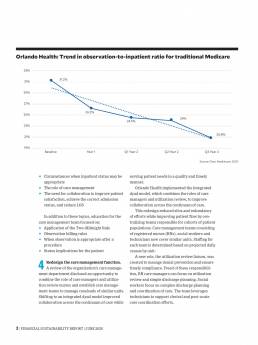

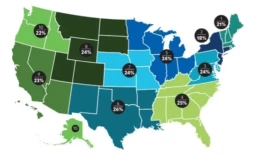

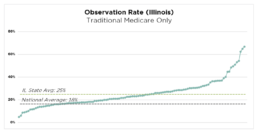

Challenged by the status determination process, many hospitals often inappropriately admit patients into observation or inpatient status. The nature of the challenge is illustrated in the exhibit below, which shows that observation rates among different CMS regions vary by as many as 8 percentage points.

Fee-for-service Medicare observation rates by CMS

Source: Analysis of publicly available Medicare fee-for-service data

Choosing the most appropriate designation is vital to ensure high-quality patient care is delivered and that financial reimbursement is appropriate for services rendered. To augment net patient revenue while prioritizing patient outcomes, hospitals and health systems should consider whether they need to improve their processes for determining patient status.

Financial implications of status determinations

Appropriate care delivery and optimal patient outcomes are the primary priorities, which can be achieved irrespective of status. Nevertheless, the ability to determine appropriate patient status and level of care has significant implications for payment.

Payer reimbursement typically differs between observation and inpatient status. While the nuances of agreements may vary across payers and facilities, reimbursement for observation discharges often is lower than for inpatient care.

Consider a standard inpatient case that may be reimbursed at about $6,500, based on CMS regulations, compared with $2,000 for a standard observation discharge. In this example, there is a $4,500 variance for a case that might have received the exact same care but was discharged with an inappropriate status. This variance is similarly prevalent with other payers, meaning documentation of medical necessity and deliberate processes for status determination can have a significant impact on net patient revenue.

On the other hand, while inpatient status potentially generates more revenue, the payer might deny that revenue and revert payment to observation status if the patient does not meet criteria for inpatient status.

Appropriate status determination and discharge status can also have significant financial consequences for the patient. A discharge from observation status may result in a higher out-of-pocket expense compared with an inpatient discharge if not performed in the most fiscally appropriate and time-dependent manner. Since observation status is an outpatient service, a Medicare patient pays 20% of billed charges as coinsurance.

However, a well-run and fiscally responsible observation stay can result in out-of-pocket expenses not unlike a daily deductible for an inpatient stay. Such an outcome depends on determining appropriate status, minimizing unnecessary testing and treatment, and expediting discharge or, if necessary, transition to inpatient status.

Best practices for observation management

Implementing the following approaches can help hospitals and health systems align care delivery and revenue cycle functions, ensuring patients are in the right status and receiving the appropriate level of care throughout their hospital stay.

Care team collaboration. Collaboration and communication among the care team members (physicians, utilization management staff and nursing staff) are critical to a successful observation management program. Keys include deliberate discussions between care teams regarding patient needs and plans of care, as well as documentation within the medical record that clearly substantiates medical necessity (see the sidebar “Observation status hinges on medical necessity,” below. A dedicated huddle to focus on observation patients also enables communication and collaboration. This huddle serves as a forum for case management, utilization management and physician advisers to review all observation patients at least once a day. It also provides an effective means for highlighting barriers to discharge, necessary follow-up actions and status conversion potential.

Status determination at the portal of entry. Determining status appropriately in the emergency department (ED) reduces the potential need for a conversion to inpatient status later in the stay and helps place the patient in the proper care setting.

In facilities with leading patient-status processes, case management or utilization management staff in the ED assume ownership of the initial status determination process. These staff are integrated into a collaborative process between ED clinicians and hospitalists that focuses on effective communication, accurate initial medical necessity reviews and timely provider documentation of patient needs and acuity.

Integration of physician advisers. A sophisticated program utilizes physician advisers as engagement liaisons between case management, utilization management, clinicians and administration. Advisers can aid in status determinations through secondary reviews of observation cases and can assist the utilization management team and physicians throughout the process. Advisers may also be involved in additional processes, including payer appeals, denials management, and education for clinicians and other quality improvement efforts.

Utilization of observation units. Dedicating provider staffing models to observation medicine ensures appropriate status designation and improves outcomes for this patient population. Much has been published on ways to implement observation-status designation, but all data point to the superiority of dedicating physician, nursing and ancillary staff to the process of observation medicine and the creation of dedicated units.

Devoting space and staffing to observation status allows the focus to remain on one type of patient and one type of medicine. Though the patients and their conditions can vary, the types of patients and conditions do not.

This uniformity allows for creation of protocols for conditions that historically tend to meet observation criteria, fitting nicely into a standardized approach. It limits variation in the general pathways for workup and treatment of these conditions, creating efficiency and, in turn, cost containment. That’s especially key for observation stays because reimbursement tends to be significantly less per patient encounter compared with inpatient status.

Dedicated observation units repeatedly have shown far superior metrics regarding length of stay and cost to the facility compared with patients in observation status who are not in a dedicated unit. Working to ensure most if not all appropriate observation patients fall under the purview of staff on dedicated units becomes a matter of not only clinical but also financial importance.

Patient outcomes are improved through the use of protocols for specific diagnoses that are tailored to short-stay observation medicine. Such protocols can eliminate unnecessary testing and potentially unwarranted treatments that could prolong the patient’s hospital stay at least and result in patient harm at worst.

Dedicated staff who consistently adhere to the same process better understand the expectations and can deliver a higher quality of care, resulting in higher patient satisfaction scores, improved clinical outcomes and, invariably, cost savings.

These savings can be seen in two distinct forms:

- On a per patient basis from the efficient workup and expedited treatment of a patient in a dedicated observation unit, specifically through less testing, consultation and patient time spent in the facility

- In reduced bed hours in the facility, thus opening beds for higher-revenue-generating patients

An urgent priority

Appropriate status determination is a nuanced process that has significant implications for patient care and reimbursement. Fortunately, the steps needed to improve this process are well within reach for hospitals.

Observation status hinges on medical necessity

Observation status is an outpatient designation that allows providers to place a patient in an acute care setting to monitor the need for an inpatient admission and diagnose and treat disease pathologies that may respond or improve quickly. Common signs and symptoms including chest pain, shortness of breath, nausea/vomiting/stomach pain and fever might result in patients being placed in observation for further testing.

Patients who have been appropriately assigned to observation status typically have much lower acuity and severity of illness compared with patients receiving inpatient care and are commonly discharged from the facility within 24 to 36 hours.

A bedded observation patient can be appropriately converted to inpatient status if needed. Medical necessity, the principle defined by CMS and other payers, establishes the distinction between observation and inpatient levels of care.

Medical necessity is documented within the medical record and should clearly and precisely illustrate the complexity of medical factors and the reasoning for the required inpatient admission. Inadequate documentation can result in payer denial of inpatient authorization and refusal of payment for services delivered.

Examples of how medical necessity can support an inpatient admission

Appropriate for observation status

- Patient complaint of shortness of breath

- Abnormal labs

- Vital signs stable

- Will need to monitor

- Consult with nephrology and cardiology

Appropriate for inpatient status

- Patient complaint of shortness of breath with imaging findings of new onset of congestive heart failure

- Lasix 80 mg IV given

- Oxygen saturation 87% on room air, improved to 100% once on 4L of O2

- Abnormal renal function, consider acute kidney injury

- Will need cardiology and nephrology consulted

- Patient appropriate for inpatient level of care, anticipate 2-midnight stay

Importance of physician documentation for patient statys

Appropriate documentation in the medical record has been a mainstay of coding and billing, and more recently the basis for determining patient status as well.

Both physicians and utilization management staff can make the best upfront determinations regarding whether a patient would be best suited for observation or inpatient status. Each patient should be viewed in totality as opposed to simply on the basis of one problem at a time. It is hence vital that as much appropriate and useful information as possible be entered into the medical record up front.

All staff — including providers and utilization management, coding and billing — must understand the various components to documentation:

- Appropriate chief complaint

- Supporting diagnoses

- Acknowledgment of physical examination

- Historical and workup findings (e.g., lab, imaging)

- Assessments of patients

- Plans for treatment and/or further workup

Documentation should support medical necessity. All who review the medical record must fully understand the primary and secondary diagnoses, the recommended treatment and additional workup, the overall level of concern for the patient, risk factors that make the patient more complex, and the patient’s anticipated trajectory during the hospitalization.

The need for comprehensive, precise documentation

The clinician must offer as many potential diagnoses as possible to support better understanding of the presented chief complaint. This list should contain all acute pathologies, including new acute conditions and chronic conditions.

Additionally, any significant comorbid disease that could factor into the level of complexity or affect the patient’s hospital stay should be mentioned in the medical record to support documentation indicating the trajectory could be longer or more complex than the presenting acute condition suggests.

Equally important is highlighting abnormal lab, imaging and vital-sign findings. If a patient has vital-sign abnormalities such as transient hypoxia, tachycardia or tachypnea, but no such acknowledgment is in the record, anyone reviewing the chart (including other clinicians) would be unable to make a fair determination about the patient’s stability or potential hospital course. Such information can be the difference between inpatient and observation status. More important, a lack of information can prevent other clinicians from efficiently ascertaining a patient’s acuity.

Why the impetus is on clinicians

It can be difficult for non-clinicians to recognize whether patients have the potential to get sicker more quickly and thus require a higher degree of services and more time in the hospital. Therefore, it is important for trained clinicians to make this distinction. This step can have important consequences for status determination.

Consider young, otherwise healthy patients with no comorbid disease who present with pneumonia. Clinicians know that in most cases, those patients very well might not need hospitalization. However, any such patients who have significant comorbid disease are at considerable risk for both failed outpatient treatment and longer hospital stays. Properly relaying the potential for higher-level needs can be the difference between observation versus inpatient status.

Hospitals face increased need amid pandemic to improve patient throughput

Hospitals face increased need amid pandemic to improve patient throughput

An acute care hospital cannot begin to be able to deliver cost-effective care if it lacks a fully coordinated approach for moving patients from admission to discharge.

Lower admissions. Higher patient days. Longer-than-average length of stay (LOS) in acute care. These are among the significant challenges U.S. acute care hospitals face as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

This problem is in part a consequence of the processes and protocols hospitals put in place to keep patients and staff safe throughout the pandemic. But it was exacerbated by the unanticipated challenges of personal protective equipment (PPE) shortages and significant increases in agency staffing and associated costs. Amid these challenges, it has become critical for hospitals to find ways to reduce LOS and enhance patient throughput. Only through such effort can they ensure their future financial and operational success and fully realize their mission of caring for the patients in their communities.

The struggle to deliver timely care

Since the start of the pandemic, hospitals have struggled to deliver care to patients in a timely manner. Dealing with longer stays in the hospital has cut into their inability to accept transfers. Meanwhile, patients face long waits in the emergency department (ED), as operational constraints have made it extremely difficult for hospitals to achieve the four-hour turnaround time for patients in the ED recommended under Medicare guidelines.

Moreover, patients who await discharge to a post-acute care setting can expect to spend significantly longer in the hospital than those awaiting discharge to the home-care setting. There are three fundamental reasons for this difference:

- An increased number of payers require prior authorization for discharge to post-acute care.

- Staffing shortages in care management departments make it more difficult for hospitals to prepare patients for discharge to the post-acute care environment.

- Most communities have limited resources to meet the increased demand for post-acute care facilities, given that both hospitals and post-acute care facilities are contending with the same staffing challenges.

These barriers, combined with supply shortages and rising input costs on labor, make maintaining effective patient throughput in short-term acute care facilities an operational puzzle for administrators of these facilities.

Hospital finance leaders have a meaningful role to play in solving this puzzle. But to fulfill that role, they must clearly understand what is involved in patient throughput, including the people and processes that are needed to ensure patients do not encounter bottlenecks on their journey from hospital admission to discharge. These considerations are addressed in the sidebar — {design: state location of sidebar}. With this understanding, finance leaders can begin to advocate best practices that can enable a hospital to optimize patient throughput, thereby ensuring patients have a positive experience with their hospital care.

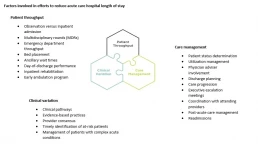

Best practices in optimizing patient time in the hospital

There are many solutions for addressing the barriers that arise throughout a patient’s hospital journey. Reducing LOS and improving patient throughput requires attention not only to the basic process steps involved with moving patients through the hospital but also to considerations around clinical variation and care management. These interlocking factors are depicted in the exhibit below.

The foremost concern is ensuring the patient receives the right care. Patients who have been assigned the wrong status may experience delays in treatment because of requirements imposed by their payers or because the diagnosis on which the patient’s status is based is of lower priority than the diagnosis that more appropriately describes the patient’s condition. Confirming that the patient is in the right status at the right time allows for the appropriate treatment to begin at the right moment. Moreover, ensuring the patient is in the right status from the point of entry helps to prevent confusion over copays, deductibles and out-of-pocket expenses once the patient leaves the hospital, regardless of the setting.

It is important to see throughput as a journey, not a destination. Although clinicians must take the lead, the ability to effectively address throughput challenges requires a team-based approach involving participation by the care team, operations, finance and transport.

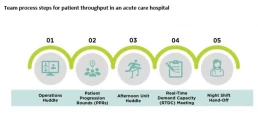

Finance leaders can play an important role by advocating for adoption of five leading practices that efficient hospitals use daily to promote effective throughput, described below and depicted in the exhibit below.

1 Operations huddle. The house operations huddle should be held in the morning, after shift change. Executives should attend this huddle for escalation purposes, while directors from all departments report out constraints they expect for the day, assess house-wide bed availability and address staffing shortages and safety and quality issues.

2 Patient progression rounds. The next step in the throughput cycle is for care team members to participate in unit-based patient progression rounds, with the goal of reviewing each patient’s treatment plan, discharge objectives and barriers to discharge. The entire care team must participate in this process to ensure patients will appropriately progress through their care while also being prepared for discharge. Once the day’s rounds are completed, the care team will be able to identify how many patients will be discharged that day and mitigate any barriers to those discharges.

3 Afternoon unit huddle. In the afternoon, care teams should gather for unit-based afternoon check-ins. This huddle gives each team an opportunity to quickly follow up on the action items from rounds, touch base on discharges expected later in the day and inform unit leaders of specific discharge barriers requiring their intervention.

4 RTDC meeting. Once the unit leaders have resolved the barriers to the extent possible, the larger team gathers for a second house-wide huddle, called the real-time demand capacity planning meeting (RTDC). The goal of the RTDC is to communicate where the remaining bottlenecks to patient throughput are and immediately address them with the appropriate leaders. Unit-based leaders should report out remaining discharges for the day, to enable transport managers to appropriately schedule the discharges and ensure requisite staff will be available. Outstanding constraints from the morning bed-huddle should be followed up during this meeting. Staffing should be addressed, test results expedited and preparations for morning discharges begun as well.

5 Night shift handoff. At end of the day, during shift change, discharge directives must be incorporated into handoff. Identifying a discharge readiness assessment and/or process into shift change continues the throughput cycle from day into night. The better the night shift understands throughput and feels the urgency to plan for discharge, the more efficient the hospital will be in continuity of its throughput. Although it may seem that a great deal of time is being spent on managing the movement of patients, it is time well spent, because next to patient safety, it is the care team’s most important responsibility.

Other steps for promoting cost effectiveness

In addition to these proposed solutions, hospital finance leaders should devote attention to other ways that hospitals can reduce LOS and streamline throughput, including:

- Focusing on improving care of patients with complex conditions who typically have long LOS

- Advocating for reducing clinical variation through development of pathways and protocols for standardized disease states

- Collecting data to track and trend discharge barriers, to continuously work toward the removal of common barriers to discharge

These solutions and leading practices are just a few pieces to the larger puzzle that hospitals must solve to improve operations and efficiencies. Success in managing throughput will remain elusive, however, without the understanding and support of the entire organization, where everyone is working toward a common goal. The pandemic may have made this truth more evident, but it remains fundamental to the success of our healthcare system under all circumstances.

Patient throughput: What it means and who is responsible for it

Patient throughput in the hospital is more than just admission to discharge for each patient. It also is everyone’s responsibility in the hospital setting. And it poses a particular challenge when one considers that patients can arrive at any of multiple portals of entry, each with their own admission protocols.

Consider the following scenario of a medical inpatient.

This patient arrives in the emergency department (ED). The emergency medicine providers determine the patient will be admitted as an inpatient to a med/surg floor – technically, this patient’s inpatient throughput timer begins when the provider writes the admission order.

Once the patient is transferred to the inpatient unit, hospitalists and specialists begin working to determine a diagnosis and projected prognosis for the patient. At the same time, the case management/discharge planner is learning about patient’s circumstances and the extent to which family support is available, while the therapy team is assessing the patient for additional discharge needs.

Once a preliminary diagnosis is assigned to a patient chart, the diagnosis corresponds to an expected geometric mean length of stay (GMLOS) per CMS. The care team continues to work together toward an expected discharge date, which should align with the expected LOS. It is important to note that a diagnosis may not be assigned to the patient until they are nearly two days into their stay. It therefore is crucial for the care team to know how long a typical patient stay would be based on the projected diagnosis, to proactively plan for discharge when no GMLOS is available.

A critical process

Throughput is the backbone for hospital LOS. It is critical to have systemwide, multidisciplinary buy-in to throughput, with all care team members being focused on treating the patient and transitioning them to the next level of care. A hospital’s ability to get patients in and out of the hospital is critical to hospital operations. In today’s environment, hospitals are experiencing a high demand in the ED as well as for elective procedures that were postponed during the pandemic and transfers requiring a higher level of care. Without efficient processes and operational support to help drive throughput, hospitals will experience significant constraints.

Implications of reduced LOS

Efforts to reduce LOS have both financial and quality implications. For payers that pay per a diagnostic-related group schedule, that payment amount reflects the patient’s expected level of care based on their diagnosis. Meeting the expected LOS ensures the payment will cover the cost of caring for the patient, and it will create capacity that ultimately allows the hospital to continue delivering care to other patients in the community.

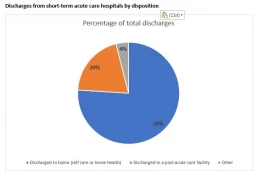

Reduced LOS also is beneficial to the patient receiving care. Research shows that the longer patients stay in the hospital, the more susceptible they are to unsafe conditions, putting them at risk for hospital-acquired conditions and other complications. These are negative quality indicators for the hospital, as well. Efficient patient care, coupled with clear communication, are paramount not only to moving patients efficiently from admission to discharge, but also enhancing the overall patient experience. As the exhibit below shows, short-term acute care hospitals in the 20th percentile in terms of quality are able to discharge a high percentage of patients to home or self-care.

Based on top 20th percentile from Medicare Provider Analysis and Review data, 2020

The Nursing Shortage in the Pandemic: Strategies to Promote a Resilient Workforce

The Nursing Shortage in the Pandemic: Strategies to Promote a Resilient Workforce

Summary

The COVID-19 pandemic served as a catalyst unlike any other to create both a labor and skills shortage in registered nurses (RNs) across the United States. There is a decreased supply of graduating nurses due to schools’ inability to accept all qualified candidates accompanied by an overall shift in RNs pursuing advanced nursing degrees. This decrease in supply is amplified by occurrences of early retirement for many nurses; over half of the nursing population is over the age of 50. As these nurses leave the workforce, they also take the skill acquired over the course of their careers. Concerns whether these impacts will negatively affect the efficacy of patient care remain in the forefront of many healthcare workers thoughts.

Introduction - Why is there a nursing shortage

The idea of a nursing shortage is not new, as the United States has experienced periodic scarcities in nursing since the 1900s. However, the current state of nurse availability has been raising voices of concern. From 2015 to 2030, more than 1 million RNs will have retired from a workforce of currently 3.8 million RNs. By the end of 2022, 500,000 seasoned RNs anticipate retiring. In addition to supply constrictions, the demand for nursing will dramatically increase. The U.S. Census Bureau reported that by 2030, the number of U.S. residents aged 65 and older is projected to be 73 million; that number is currently 54 million.

As the older generation of nurses retire, they are no longer able to pass their knowledge to up and coming nurses, leading to concern over a skills shortage. This has the potential to impact the education of new nurses, which raises alarm for the effect on patients. More than 75% of RNs believe the nursing shortage presents a major problem for the quality of their work life, the quality of patient care, and the amount of time nurses can spend with patients. In recent studies, 98% of nurses see the shortage in the future as a catalyst for increasing stress on nurses, lowering patient care quality (93%), and causing nurses to leave the profession (93%).

Decreased Supply in Graduating Nurses

Since the beginning of the pandemic, nursing schools have faced difficulty in obtaining hands-on experience for their students due to hospitals restricting access for anyone to limit the spread of germs. Hospitals began shutting down clinical rotations during COVID, unable to afford to spend valuable time and equipment on students, while simultaneously overworking veteran nurses. Some states like California decreased the number of required clinical hours after some nursing schools went fully remote.

Many schools are facing decreased aid from the government. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services is reducing funding for nursing schools due to an internal error that occurred 10 years ago. The error caused for an estimated $1 billion for about 120 colleges.

Appropriate patient status determination and discharge status can also have significant financial implications for the patient. A discharge from observation status may result in a higher out-of-pocket expense to the patient compared to an inpatient discharge. Since observation status is an outpatient service, a Medicare patient pays 20% of billed charges for coinsurance.

Pursuance of Advanced Degrees

An additional reason for the lack of RNs is the rise in nurses pursuing advanced degrees. From 2010 to 2017, the increase in nurse practitioners reduced the size of the RN workforce by approximately 80,000 nurses. ,175,000 RNs per year are needed and only about 155,000 graduate per year. 28,000 RNs are becoming NPs per year. Between 2008-2016, the percent of primary care providers in rural areas that were Nurse Practitioners jumped from 17.6% to 25.2%; Urban areas grew from 15.9% to 23.0%. This gives the potential for surpluses of NPs.

Increased Occurrences of Early Retirement

The COVID-19 pandemic served as a mechanism for nurses bordering retirement to decide to leave the workforce prematurely. The American Nurses Association predicts that 500,000 seasoned RNs anticipate retiring by 2022, and the US Bureau of Labor Statistics projects more than 1 million new RNs are needed for expansion and replacement of experienced nurses. Many nurses have taken on the increased emotional burden of becoming sole support systems for patients in their dying hours, many of whom could not see their families. 67% of surveyed travel nurses responded that they felt the healthcare system did not prioritize nurses’ health and mental well-being. In Mississippi, nurses are retiring early to avoid burnout: 2,000 fewer nurses than the beginning of 2021, not to mention the 6,000 vacancies they had prior. Two-thirds of nurse’s state their experiences during the COVID-19 crisis have caused them to consider leaving nursing. The supply of nurses is not meeting the demand, and the disparity is amplified by the fact that nursing schools cannot viably accept all qualified candidates.

Covid Impact on Nurses

As of 2021, approximately one in eight nurses had not gotten a Covid-19 vaccine nor do they plan to get one. A Texas hospital system had 153 people resign or were fired after refusing to get vaccinated. As the virus continued to spread, the American Association of Critical Care nurses conducted a survey showing two thirds of critical care nurses were considering quitting their jobs as well 67% of those surveyed were fearful of taking the virus home to their families. Nurses are reporting an overall decrease in career satisfaction in not only acute care facilities but long-term care and hospice settings as well.

Nurses have been forced to navigate through human and financial constraints, interpersonal conflict, and hostile work environments as the pandemic continued to move into its second year. This laid the foundation for nurses to leave the bedside, experience extreme burnout, mandatory overtime, and the inability to provide adequate patient care. Emotional and physical exhaustion, in addition to lack of personal accomplishment is a source of burnout which can lead to secondary trauma. Experiencing trauma leads to lack of sleep, poor appetite, job dissatisfaction and the inability to cope putting nurses at risk for post-traumatic stress disorder. Traumatic experience has been associated with having to prioritize who gets care and the high number of deaths.

Professional quality of life can be affected by both positive and negative aspects. It is not uncommon for someone to feel burnout in many aspects of life, but understanding burnout related to working in healthcare during a pandemic is very distinct. Burnout comes from the work nurses do and can manifest in very distinct ways which can have an impact on the people they are caring for. The current dynamics are 1) increased traumatic stress related to the pandemic, 2) cumulative grief with so much loss and death, 3) moral distress as nurses are having to practice differently challenging their ethics and what does not feel right.

Nurse leaders are also experiencing a high level of stress as the job demands increase and organizational constraints continue to soar. Constraints such as lack of beds, increased staffing ratios due to nurses leaving, and a large span of control. Leaders face not only patient and staff concerns but organizational constraints as well. Limited human and financial resources, interpersonal conflict, and a hostile work environment are also causes of nurse leader stress. Other concerns include the adoption of new staffing models to adapt to the shortage of nurses as well as how best to recognize nurses’ contributions to the difficulties of today’s work environment.

Strategies for building a resilient nursing workforce

Finding joy in work is rare in this current work environment which has led to job dissatisfaction, lack of employee engagement, and a sense of well-being. This is not a new problem for nursing but one that has been grossly exacerbated by the pandemic. Burnout is an occupational phenomenon and not necessarily an individual’s problem; however, individuals must be healthy and resilient to the secondary trauma that occurs as part of the work. Therefore, strategies to create a resilient workforce require both support from organizations to create healthy work environments and nurses to practice individual resilient building skills.

A healthy work environment includes adequate staffing, strong collaboration, communication, authentic leadership, recognition that is meaningful and autonomy for the staff to make their own decisions. In order to achieve a healthy work environment, organizations must empower staff, which requires transformative leadership and shared governance. Many of these elements of healthy work environments are found in Magnet organizations or units that have been designated Beacon awards – highlighting these key elements of how to achieve well-being from an organizational perspective.

In addition to workplace health, individuals must practice increasing their own compassion through personal resilience building to counterbalance the risk of burnout. Of importance to note, practicing resilience should not be done to build barriers against a poor work environment. Instead, resilience – or the ability to grow and adapt from adversity – should be done to have strength against the potential hardships that are witnessed in caregiving, such as death, loss, suffering, and pain. Personal resilience building skills can include practicing gratitude, mindfulness or meditation, journaling or debriefing through writing, or self-care, such as exercise. These activities are valuable moments to pause and reflect on the importance and significance of the work of nursing and the contribution caregivers bring to the quality of patient’s lives. In practicing resilience building activities, nurses can potentially decrease burnout and secondary stress, which can lead to a longer, more fulfilling career in nursing.

1 https://www.aacnnursing.org/news-information/fact-sheets/nursing-shortage

2 https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/workforce/

3 https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2019/12/by-2030-all-baby-boomers-will-be-age-65-or-older.html

7 https://www.kff.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2012/08/facultyshortagefs.pdf

8 https://www.aacnnursing.org/news-information/fact-sheets/nursing-faculty-shortage

9 https://www.statnews.com/2021/02/10/biden-administration-nursing-schools-pay-for-government-mistake/

10 https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/abs/10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00686

14 https://www.businessinsider.com/nurses-havent-gotten-covid-19-vaccine-causing-staff-shortages-2021-8

Navigating Observation Level of Care & Appropriate Patient Status Determination

Outpatient Observation Management – Impact on Financial Cost & Best Practices

Placing a patient in the most appropriate level of care is important to ensure the patient is cared for with the right level of services and the hospital is reimbursed appropriately for services rendered. However, many hospitals are challenged by the status determination process, and often over utilize the observation level of care. According to publicly available Medicare data, the national average observation rate (the ratio of bedded observation to inpatient cases) was 18% in 2019. The state average observation rate for Illinois facilities in the same period was 25%. This means that most short-term acute care facilities in Illinois had an observation rate that exceeded the national average (Figure 1). There are considerable financial implications to patient discharge status, which often results in missed revenue. Hospitals and health systems should consider implementing status determination process improvements to augment net patient revenue while prioritizing patient outcomes.

Figure 1: Traditional Medicare Observation Rates for Illinois short term acute care facilities

Source: Publicly available Medicare data. Represents Traditional Medicare only.

Observation Status and Medical Necessity

Observation status is an outpatient designation that allows providers to place a patient in an acute care setting to monitor the need for an inpatient admission. Common signs and symptoms including chest pain, shortness of breath, nausea/vomiting/stomach pain and fever might result in placement in observation for further testing. Appropriate observation patients typically have much lower acuity and severity of illness compared to inpatient level of care, and are commonly discharged from the facility in observation status within 24-36 hours.

A bedded observation patient can also be appropriately converted to inpatient status if there is evidence of medically necessary care. “Medical necessity”, the principle defined by CMS and other payors, establishes the distinction and substantiating evidence between observation and inpatient levels of care. Medical necessity is documented within the medical record, and should clearly and precisely illustrate the complexity of medical factors and the reasoning for the required inpatient admission (Figure 2). Inadequate documentation can result in payor denial for inpatient authorization and refusal of payment for services delivered. Physician documentation is the cornerstone for appropriate status determination, and there can be significant financial implications to the chosen level of care.

Figure 2: Example of How Appropriate Medical Necessity Documentation Can Support an Inpatient Admission

Observation Appropriate

- Patient complaint of shortness of breath

- Abnormal labs

- Vital signs stable

- Will need to monitor

- Consult Nephrology and cardiology

Inpatient Appropriate

- Patient complaint of shortness of breath with imaging findings of new onset of congested heart failure

- Lasix 80mg IV given

- Oxygen saturation 87% on room air, improved to 100% ounce on 4L ofO2

- Abnormal renal function consider, acute kidney injury

- Will need cardiology and nephrology consulted

- Patient appropriate for inpatient level of care anticipate 2 midnight stay

Financial Implications of Observation Management

Delivery of care and outcomes are the priority. But appropriate patient status and level of care determination can significantly affect net revenue. Payor reimbursement (for both government and private payors) typically differs considerably between observation and inpatient status. While the nuances of payor agreements may vary across payors and facilities, reimbursements for observation discharges are often lower than inpatient payments While this reimbursement differential can vary, a typical Traditional Medicare case can provide an illustrative example. CMS IPPS and OPPS final rules stipulates that a standard inpatient case is reimbursed approximately $6,500, while a standard observation discharge is reimbursed approximately $2,000. In this example, there is approximately a $4,500 reimbursement variance for a case that might have received the exact same care, but was discharged in an inappropriate status. This positive reimbursement variance is similarly prevalent with other government and private payors. Across most payors, documentation of medical necessity and deliberate processes for status determination can have a significant impact on net patient revenue.

Appropriate patient status determination and discharge status can also have significant financial implications for the patient. A discharge from observation status may result in a higher out-of-pocket expense to the patient compared to an inpatient discharge. Since observation status is an outpatient service, a Medicare patient pays 20% of billed charges for coinsurance.

Observation Management Best Practices

There are several ways that a facility can align care delivery and revenue cycle functions through level of care and status determination processes.

Care Team Collaboration

Collaboration and communication among the care team members (providers, utilization management, and nursing staff) is critical to a successful observation management program. This includes deliberate discussions regarding patient needs and plan of care between care teams. This also includes documentation within the medical record that clearly substantiates the medical necessity. A dedicated huddle to focus on observation patients also enables communication and collaboration. This observation huddle serves as a forum for Case Management, Utilization Management and Physician Advisors to review all observation patients at least once per day and is an effective method to highlight any barriers to discharge, necessary follow-up actions, and status conversion potential.

Status Determination at the Portal of Entry

Appropriate status determination from the Emergency Department reduces the need for conversion to an inpatient status later in the stay and helps place the patient in an appropriate care setting. Facilities with leading patient status processes dedicate Case Management/Utilization Management staff in the emergency department to own the initial status determination process. These staff should be integrated into a collaborative process between ED providers and hospitalists that focuses on effective communication, accurate initial medical necessity reviews, and timely provider documentation of patient needs and acuity.

Utilization of Observation Units

When observation cases are bedded on inpatient units, care teams often have difficulty differentiating between patients placed in observation status or inpatient status. This results in longer lengths of stay for observation cases, and increased resource utilization for observation care. A hospital can delineate patient status assignments by implementing a unit focused exclusively on observation patients. Sometimes these units are within or adjacent to emergency departments. This enables the care team to automatically differentiate observation patients from other bedded patients. It also allows for increased monitoring of observation patients (recommended rounding 3x per day vs 1x per day). Sometimes facilities will introduce diagnosis-specific algorithms to aid in this colocation process, including chief complaints such as chest pain, syncope and collapse, heart disease, cellulitis, and headaches. If a dedicated observation unit is not possible, providers and transfer centers should attempt to cohort observation patients as much as possible.

Physician Advisor Integration

A sophisticated Physician Advisor (PA) program utilizes the PA resource as an engaging liaison between Case Management, Utilization Management, providers, and administration. The PA can aid in the status determination process through secondary review of the observation cases, and can assist the UM team and providers through the documentation process. The PA may also be involved in additional processes including payor appeals, denials management, education for providers, and other quality improvement efforts.

The Value Journey: Improving Cost Structure Through Performance Improvement

The Value Journey: Improving Cost Structure Through Performance Improvement

Feature: Victor G. DeMarco, CPA, Barton S. Richards, MBA, CHFP, Larry Volkmar, RN, BSN, MBA, FACHE, and Lauren C. Gorski, MBA, MHSM

A New York hospital offers a case example of how to undertake performance improvement on a systemwide scale to prepare for value-based care.

In 2012, Bronx-Lebanon Hospital Center in New York began preparing for the shift to a value-based payment system by performing a complete review of its operations. This internal organizational review provided the organization’s senior executives with clear evidence that the hospital was operating efficiently, in both fixed and variable cost structures. Despite the apparent strength of the organization in its current state, however, the senior executives acknowledged that the emerging value-based healthcare environment would present new complexities that would challenge the organization’s ability to maintain financial stability in the future. They therefore undertook an initiative to verify the organization’s current operational efficiencies and explore new cost-saving opportunities.

Bronx-Lebanon Hospital Center is the largest not-for-profit health system serving the South and Central Bronx, with 972 beds at two major hospital divisions, comprehensive psychiatric and chemical dependency programs, two specialized long-term care facilities, and an extensive BronxCare Network of practices that provides more than 1 million outpatient visits annually. Its emergency department (ED) also sees about 141,000 visits annually, making it among the busiest in New York. It serves a patient population with high disease incidence rates, large numbers of minorities and immigrants, and low socioeconomic status. Much of the South Bronx is also designated as a medically underserved and health professional shortage area.

This initiative was conducted in two separate phases to identify savings and efficiency opportunities. The first phase involved an in-depth assessment of variable costs, such as supplies and contracted services, and the second phase focused on employee and provider productivity.

Once savings and efficiency opportunities were identified, it was decided that changes should be implemented immediately to stay ahead of the changing healthcare landscape. By 2015, improvement opportunities identified and implemented as a result of the initiative amounted to $20 million in cost savings and operational efficiencies. What follows is an account of how Bronx-Lebanon was able to achieve these results.

Uncovering and Implementing Nonlabor Cost Savings Opportunities

During the first phase of the project, each department’s variable-cost structure was analyzed for areas of opportunity. Focus teams, which included an executive sponsor and the department director or manager, were created for each initiative. The teams were tasked with identifying areas of cost savings and efficiency opportunities in each department, looking at everything from supply costs to clinical practices to services contracts. As a result, major initiatives were undertaken in areas such as the pharmacy, medical-surgical supplies, contracted services, employee benefits, support services, and the laboratory. The following discussion focuses on four of these areas.

Pharmacy. The focus team charged with improving pharmacy performance achieved notable success using a process that began with a thorough assessment of pharmacy operations. This assessment included an in-depth review of the department’s policies and procedures, purchase orders, chargemaster, and usage data. The team also was able to formulate conclusions by observing the pharmacy’s day-to-day processes and interactions with clinical staff, including models of care, operations, cost-reduction opportunities, drug distribution, inventory reduction, and physician relations. As a result of reviewing the usage data, the team recommended that therapeutic substitutions of clinically equivalent pharmacy products be made, including in the areas of proton pump inhibitors and cervical ripening agents. Support for these changes was bolstered through education aimed at raising awareness by the clinical staff, and adjustments were made to the hospital’s formulary.

As a result of this assessment, the focus team undertook three primary initiatives involving collaboration with pharmacy, clinical, regulatory, and finance staff.

First, to better serve the needs of the community, Bronx-Lebanon partnered with a local retail pharmacy to address the needs of the hospital’s patient population, particularly with respect to home prescription delivery and payment options. This initiative sought to improve medication adherence in the hospital’s low-income population, thereby helping to reduce readmissions and redirect patients from the emergency department (ED) to an outpatient practice.

Second, Bronx-Lebanon worked with the lead physician to develop a program that would address the needs of patients who were directed to receive injectable medications for multiple sclerosis. The program brought injectable drug preparation and the infusion process in-house, ensuring that patients were kept consistently under the care of their existing provider. This change also resulted in the creation of a new revenue stream.

Third, the team facilitated collaboration between pharmacy and clinical staff on an educational initiative aimed at reducing utilization of certain high-cost drugs by raising physician awareness of clinically equivalent substitutes and utilization guidelines. By working with a physician leader from the hospital and utilizing third-party clinical experts, the team was able to increase physician participation. Committee meetings and educational sessions were held on a regular basis to keep clinical leadership apprised of changes and include them in the decision-making process.

Together, these pharmacy-focused initiatives enabled Bronx-Lebanon to improve Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) and pay-for-performance measures and keep the pharmacy on track to meet its budget.

Medical-surgical supplies. Another focus team was able to realize significant savings through an operating room (OR) inventory project. In partnering with materials management and OR personnel, the team performed a complete assessment of the current OR medical-surgical supply inventory. The assessment included reviews of supply usage data, purchase orders, and on-hand inventory data. The team developed a system that allocated inventory into four categories:

- Obsolete (not used or purchased in 12 months)

- Excess (greater than a year’s supply on hand)

- Slow moving (greater than three months’ supply on hand)

- Active

This process allowed the team to focus first on eliminating obsolete and excess inventory before undertaking a complete redesign of the OR storage room and processes. The process provided the groundwork for installing storage equipment and implementing a categorized, cataloged system designed to achieve efficiencies, with PAR levels (i.e., minimum quantities stocked before products would automatically be reordered) set for each inventory item. The team also worked with the surgeons to identify their product preferences, and the variety of products was reduced. Slow-moving and obsolete inventory also were eliminated.

The laboratory. The focus team charged with improving performance in the laboratory also demonstrated how a collaborative approach could produce a positive impact on the hospital’s variable-cost structure. The team not only was able to negotiate better pricing on contracts in areas where there was clearly increased usage, such as the blood and reference lab, but also was able to achieve similar results in other areas where the opportunities were not so clear. Specifically, the team analyzed reagent supplies and testing equipment for usage and effects on productivity through observation and data analysis, and was able to identify significant opportunities in these areas, including the optimization of Bronx-Lebanon’s group purchasing contracts to obtain better pricing on reagent supplies and the acquisition of new equipment that would improve labor productivity. This new equipment required less staff time to operate than the equipment that had been in use.

Support services. The performance improvement efforts that focused on support services, such as biomedical maintenance, dietary, and linen, achieved significant results. The hospital had been using outsourced providers in these areas.

The team considered the total cost elements involved and the micro-economic drivers as part of its effort to analyze costs associated with each service. The team also sought to understand which cost levers to pull and the impact any change would have on overall quality and costs. In the area of food and nutrition, for example, improved quality, make-fresh-versus-buy options, labor inputs, retail pricing, and nursing unit food PAR levels should be considered when undertaking a performance improvement initiative.

Ultimately, the team decided to expand the scope of the biomedical maintenance contract to take over additional equipment, shifting the risk from Bronx-Lebanon to the service provider. Utilization changes were made based on the review of dietary services data to reduce the hospital’s waste. Again, the leadership for these areas was vital in achieving optimum results, with hospital leadership taking on a pivotal role in ensuring that changes were implemented in a timely manner, with appropriate communication to staff and stakeholders, negotiations with suppliers, and changes to processes.

In the nonlabor areas, Bronx-Lebanon’s approach of managing multiple initiatives across its organization resulted in upgraded processes with improved efficiencies, ultimately producing a substantial positive impact on the hospital’s financial performance. The key to success was maintaining a coordinated effort driven by the organization’s major stakeholders. Bronx-Lebanon’s senior management and administrative team were deeply involved throughout the nonlabor phase of the project, holding biweekly steering committee meetings in addition to frequent sub-committee meetings to ensure that the focus areas were continually moving forward. Focus team leaders assumed responsibility for driving cost savings within their respective areas and played an active role in supplier negotiations. Finance staff played an important role in each initiative as well, monitoring progress and providing the project teams with updates including savings impacts to date and quality results. The coordinated effort and buy-in at all levels of the organization resulted in a successful phase of the project.

Uncovering and Implementing Labor Productivity and Efficiency Opportunities

Prior to the start of the project, Bronx-Lebanon maintained an aggressive vacancy control process, concentrating on limiting the amount of contracted resources. With upwards of 4,000 employees, including over 400 salaried physicians, the hospital faced challenges in maintaining consistency and productivity across different locations and service lines.

Under the oversight of Bronx-Lebanon’s senior management, productivity analyses were conducted, focusing on the roles most prevalent across the organization, such as registrars and managers. Staffing productivity savings were identified through benchmarking and volume trend analyses.

In-depth analyses of each service line’s functionality were performed to assess margin contribution. To start, all direct and indirect costs were analyzed, including volume trends over time compared with staffing. Revenues were then assessed to determine the feasibility of sustaining service lines.

A proportional span-of-control review also was performed, which involved identifying staff-to-executive ratios across all areas of the organization. Close attention was given to positions with minimal reporting relationships at the manager and director level. In looking at each department, opportunities to consolidate oversight were considered and staffing adjustments were made to contribute to a flatter staff-to-executive ratio. Through this process, the team identified redundant programs and departmental activities that could be consolidated.

Streamlining the span of control and combining responsibilities enabled the organization to achieve productivity savings. Physician champions for each service line became pivotal in identifying how specific areas could function with optimal staffing during each part of the day.

For example, the chairman of family medicine implemented new processes throughout his department based on an analysis of the data that allowed for the consolidation of responsibilities and the implementation of increased efficiencies, thereby significantly improving productivity.

Such changes were implemented in phases, starting with administrative staff roles and proceeding through clinical roles, and team leaders worked within their respective divisions to maintain systemwide standards for education and goal awareness.

The most challenging piece of the project was the analysis of physician productivity. For each physician, a provider productivity analysis was completed by location and specialty, including patient visit trends, revenue generation, and total compensation. Each physician’s performance was then benchmarked against national standards, and targets for visits by provider on an outpatient basis were identified.

The analysis took into account each physician’s specific role as an important consideration. Many physicians had unique roles, serving in various instances as chairmen, division chiefs, or medical educators for residents. To reach optimal productivity with its physicians, Bronx-Lebanon is considering a broad range of recommendations, including dedicated inpatient hospitalist and ancillary service models.

Results

Through both the nonlabor and labor phases of its performance improvement project, Bronx-Lebanon was able to achieve more than $20 million in total benefits. The 12-month initial, nonlabor phase of the project yielded savings of more than $5 million in pharmacy initiatives and an additional $6 million from reductions in variable costs, including human resources, ancillary services, support services, purchased services inventory, and supply expenses. The five-month second phase of the project, focusing on labor, achieved $9 million in productivity increases, including $4 million for physicians, $2 million for management and support personnel, $1 million for nonphysician providers, and an additional $2 million in other areas.

Bronx-Lebanon’s improved operational efficiencies have moved the organization closer to becoming a value-based health system and provided a basis for its future continuous growth. The hospital also has recently been selected by the New York State Department of Health as a performing provider system lead for the state’s Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment program, providing the hospital with an additional opportunity for healthcare performance improvement.

Success Factors and Lessons Learned

Performance improvement is an ongoing effort. Based on their experience with Bronx-Lebanon’s comprehensive performance improvement project, the hospital’s senior executives cite three key lessons that they regard as being critical to any such project’s success.

First, the initiatives must be visible throughout the organization, with their importance clearly highlighted and communicated so they are apparent to all staff.

Second, buy-in and staff participation are required, and senior leadership must play an active role in implementation. When new efficiencies are discovered through collaborative efforts such as those that characterize Bronx-Lebanon’s initiative, senior executives should be prepared to move quickly in advancing these changes and improvements to the organization.

Third, performance improvement initiatives can be effectively identified and implemented only through such a collaborative, structured approach, which should be reinforced through ongoing project governance at the senior-leadership level.

On a more specific level, five keys to success can be gleaned from Bronx-Lebanon’s experience:

- Collaboration with physician leaders across service lines, providing strongly data-based support for their decision making

- Inclusion on project teams of individuals who have a familiarity with leading practice models that can be implemented within a short time frame

- Team leadership by individuals who have sufficient communication skills to clarify complex issues for management, thereby promoting expeditious decision making

- Thoroughness in communications aimed at overcoming resistance to change, including educational sessions, one-on-one meetings, regular status updates, and formal steering committee meetings

Strong sponsorship by senior leadership, particularly with regard to labor productivity.

Victor G. DeMarco, CPA, is senior vice president and CFO, Bronx-Lebanon Hospital Center, Bronx, New York, and a member of HFMA’s Metropolitan New York Chapter.

Barton S. Richards, MBA, CHFP, is managing director, The Claro Group, Chicago, and a member of HFMA’s First Illinois Chapter.

Larry Volkmar, RN, BSN, MBA, FACHE, is managing partner, The Claro Group, Chicago.

Lauren C. Gorski, MBA, MHSM, is manager, The Claro Group, Chicago, and a member of HFMA’s First Illinois Chapter.

Publication Date: Wednesday, June 01, 2016